Eastern Indigo

Eastern Indigo

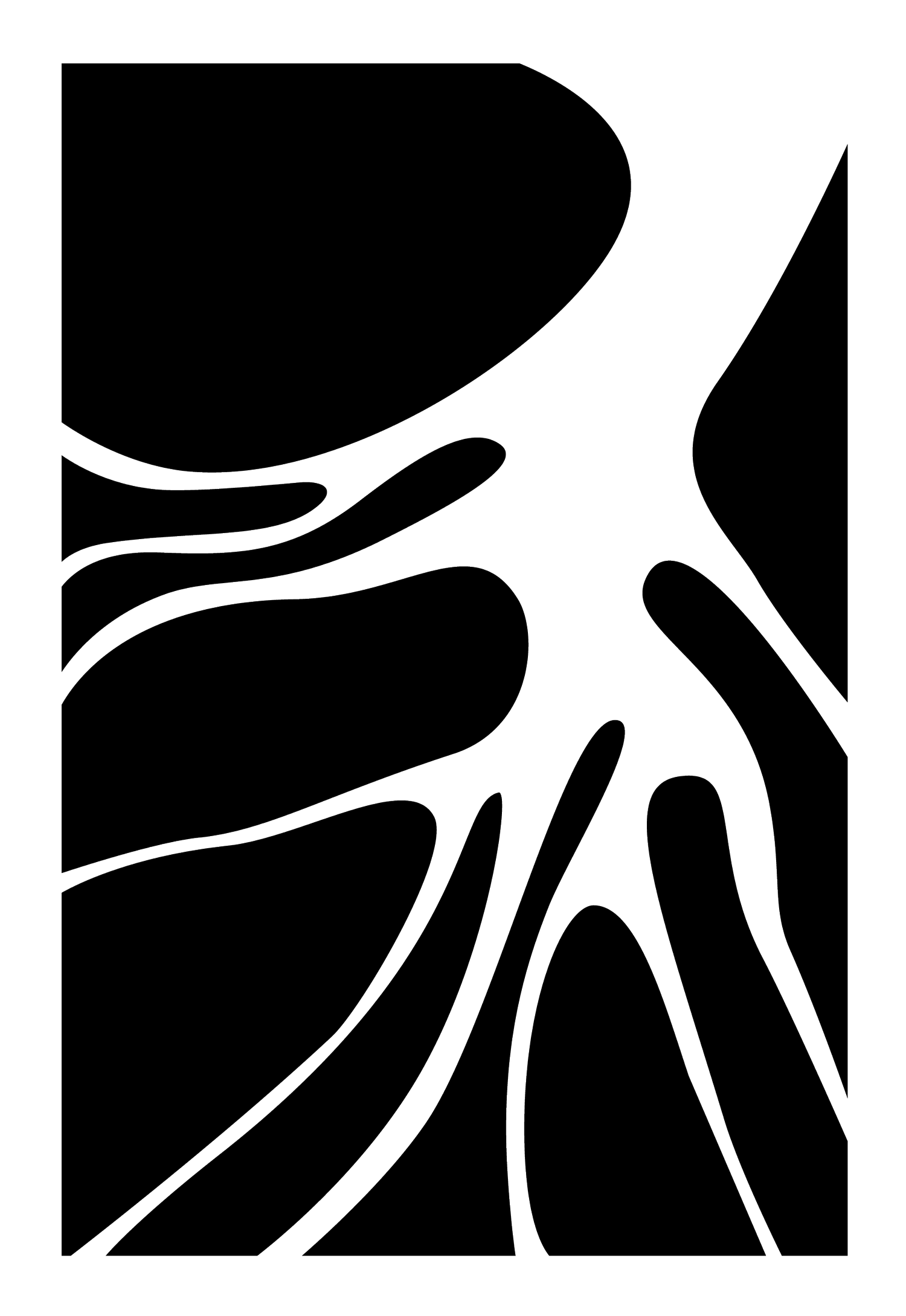

Klamath Siskiyou Forest Ditpych : Old Growth

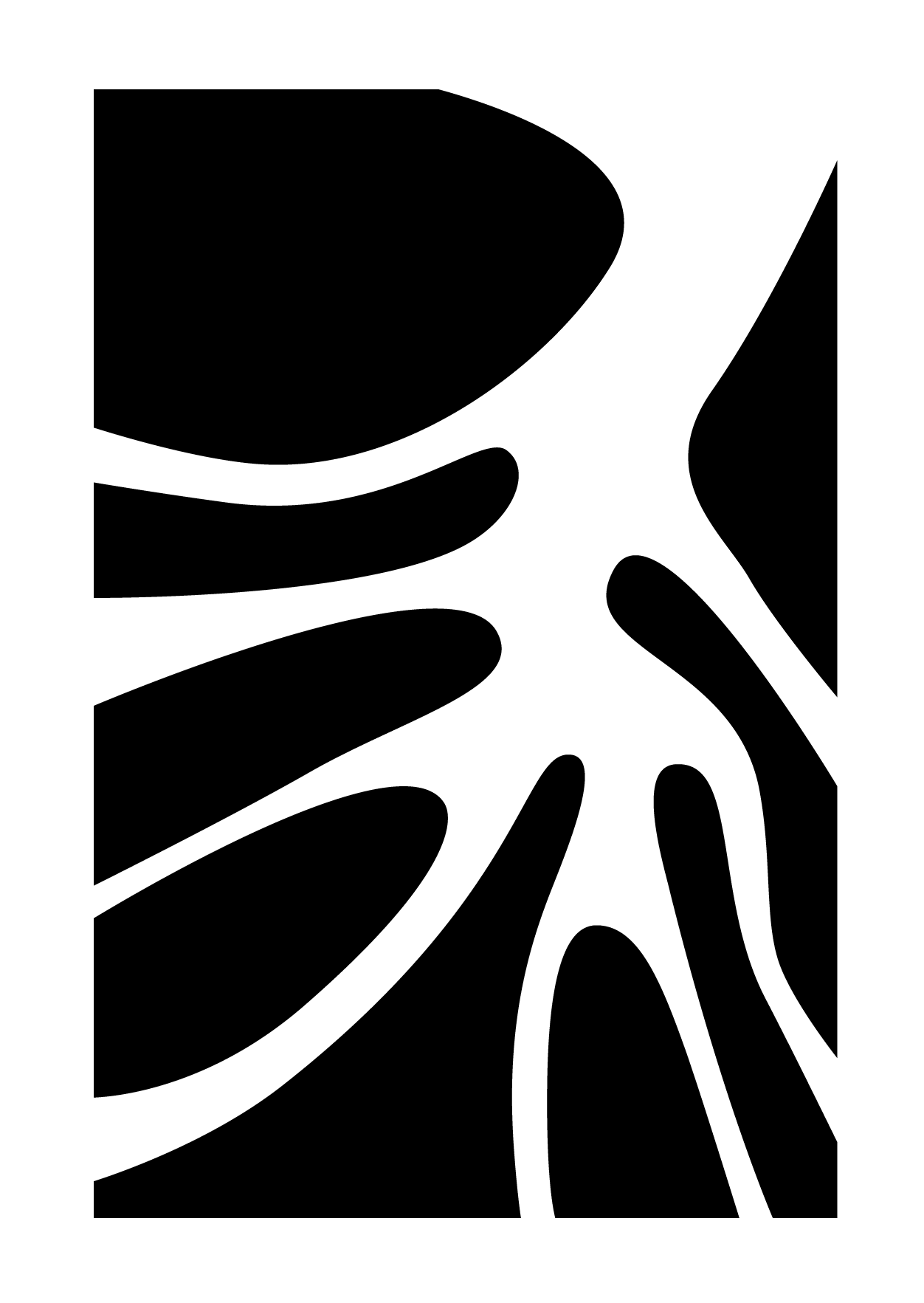

Klamath Siskiyou Forest Ditpych: Post Fire

Owls of the World

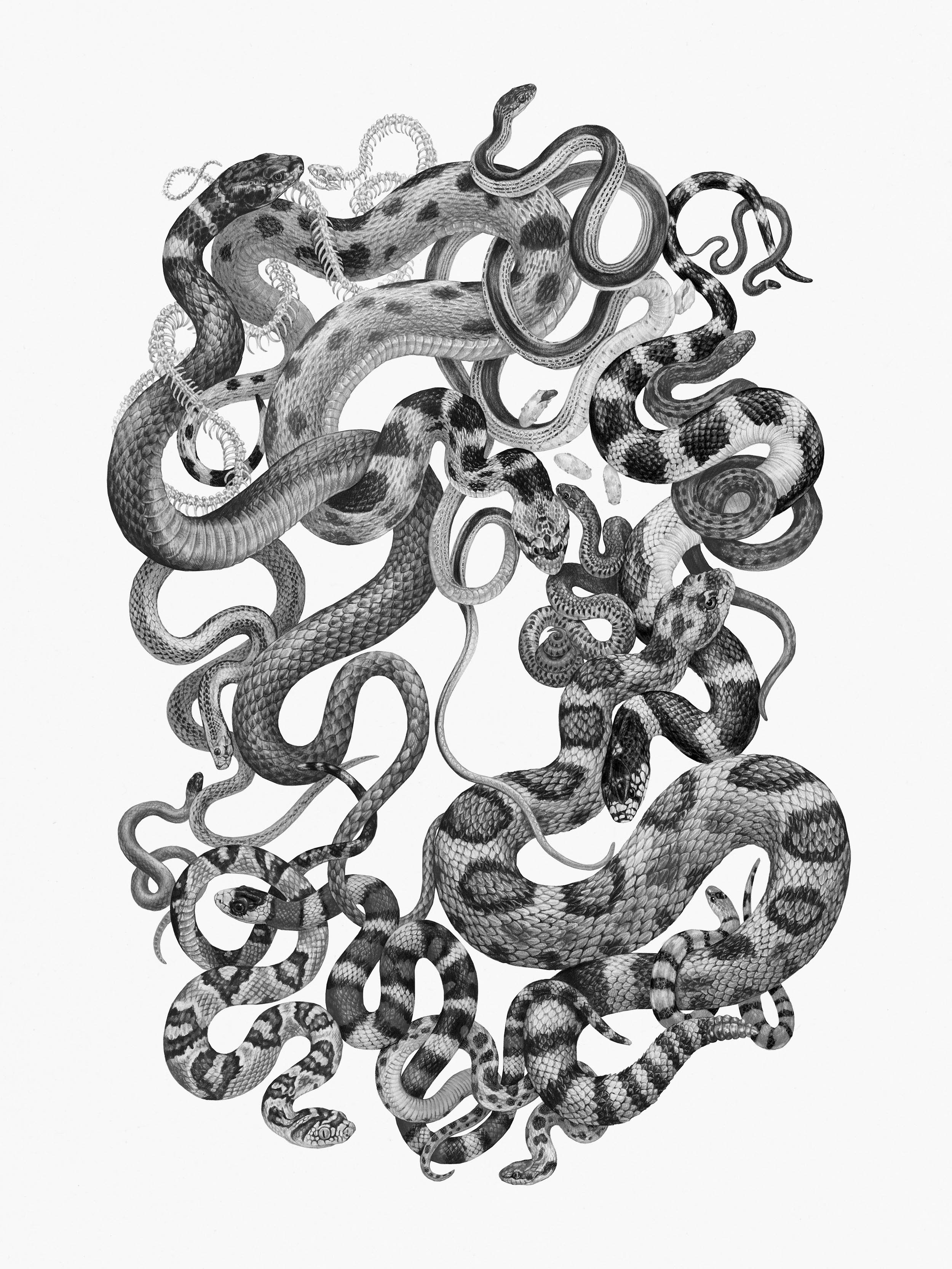

Zion National Park Biodiversity Series: Snakes of Zion National Park

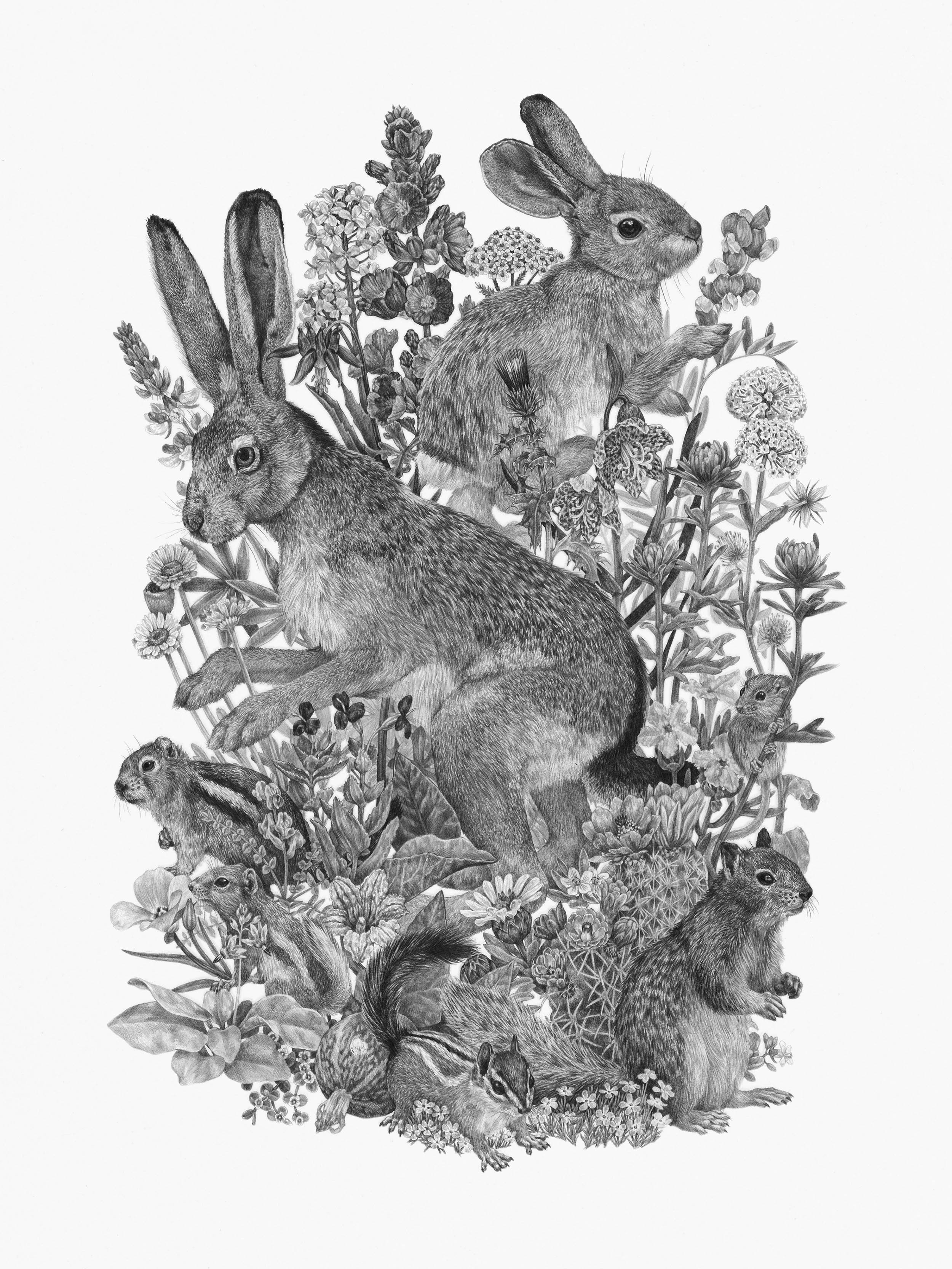

Zion National Park Biodiversity Series: Common Small Mammals and Wildflowers of Zion National Park

On Eastern Indigo and Others

Eastern Indigo

27.5” x 36” (69.9 x 91.4 cm), Graphite on paper, 2020

A Threatened Eastern Indigo snake wraps itself around five species of pitcher plants, carnivorous plants that flourish in the pitcher plant bog microhabitats found through-out Longleaf Pine ecosystems. Species: Eastern Indigo Snake Drymarchon Couperi, Pitcher plants, clockwise from top right: Whitetop Pitcherplant Sarracenia leucophylla, Parrot Pitcherplant Sarracenia psittacina, Hooded Pitcherplant Sarracenia minor, Yellow Pitcherplant Sarracenia flava, Green Pitcherplant Sarracenia oreophila

This piece is a part of my ‘Longleaf Pine’ series. About this series: Longleaf Pine forests once covered 90 million acres in the Southeast, stretching from Virginia to Florida, and west into eastern Texas. Today, only three percent of the original forest remains, lost to hundreds of years of commercial logging, fire suppression, the conversion of forest to urban development and livestock grazing, and the replanting of forests with faster growing species of pine. These rich forests are dominated by their namesake Longleaf Pine, an evergreen conifer that grows 80 to 100 feet (24 to 30 meters) tall and has leaves that can grow up to 18 inches (46 centimeters) long. But there is much more to these forests than Pinus palustris; mature Longleaf Pine savannas can contain up to 40 species of plants, making them one of the most diverse plant communities on the globe. Even in their fragmented state, remaining stands of Longleaf Pine forest harbor almost 200 species of birds and hundreds of animal species. More than 30 of these species are endangered and threatened, including two species of snakes that have been designated as Threatened at the federal level: the Eastern Indigo Snake and Black Pine Snake. Although it has not yet received federal designation, the fate of the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake is inextricably linked to that of the Longleaf Pine ecosystem, and has declined with the loss of its habitat. The three pieces in this Longleaf Pine forest series explore these at- risk snakes and the species they share Longleaf Pine forests with.

The illegibility is meant to acknowledge the challenge of endeavoring to make something lasting, and the project chooses to hope that we can still reach each other somehow. Even if much of what we do sinks back into the earth, traces remain.

Klamath Siskiyou Forest Ditpych

Old Growth

45" x 60" (114 x 152 cm), Graphite on paper, 2018

Post Fire

45" x 60" (114 x 152 cm), Graphite on paper, 2018

The work for my solo show ‘Forest’ was inspired by the flora and fauna of the Klamath-Siskiyou region of Oregon and California. The two pieces of the show’s central diptych, ‘Old Growth’ and ‘Postfire,’ focus on vital points in the life-cycle of Klamath- Siskiyou forests: mature old-growth, and complex early seral, the stage of forest life that follows a disturbance like wildfire. By highlighting the fascinating and at-risk species that are dependent upon these stages of forest development, these two pieces underscore the importance of protecting forests at every stage of growth. Notes and photographs that inspired this diptych were gathered during Signal Fire’s Wide Open Studios Klamath National Forest trip in the summer of 2017. (Longer statements are available for each drawing in the series if desired.)

Owls of the World

18” x 24” (46 x 61 cm), Procreate, 2020

The haunting call of an unseen owl has long been the stuff of legends. Found on every continent except Antarctica, the world's 200 owl species have adapted to thrive not only in forest habitats, but also in deserts, on tropical islands, and in the frigid Arctic tundra. These predatory, primarily nocturnal birds vary widely in size. The world's largest owl, the Blakiston’s Fish-Owl, has a wingspan that is just shy of six feet (two meters). (Researchers explain that it is so large that it is "...commonly mistaken for a person...or something out of a dream...”) The world's smallest owl, the minute Elf Owl, barely weighs 1.6 ounces (45 grams). Of the 244 species of owl recognized by the IUCN Red List, four are listed as Critically Endangered, thirteen as Endangered, twenty-eight as Vulnerable, and twenty-six as Near Threatened. Threats to global owl biodiversity are wide ranging, but according to IUCN Red List data the primary drivers of owl species decline are logging and wood harvesting, and agricultural development. Residential and commercial development, roads and railroads, and the climate crisis also put owls at risk.

Zion National Park Biodiversity Series

Snakes of Zion National Park

18” x 24” (46 x 61 cm), Graphite on paper, 2019

Common Small Mammals and Wildflowers of Zion National Park

18” x 24” (46 x 61 cm), Graphite on paper, 2019

My Zion National Park Biodiversity series was based on my experience as an Artist in Residence with Zion National Park. I spent mid-October to mid-November of 2018 living in Zion, in the historic Grotto House not too far from Angel’s Landing. My days were spent hiking from sun-up to sun-down, photographing, taking notes and sketching. At night, I would pour through the materials that I had gathered and do my best to identify the species that I had encountered. I was surprised that even so late in the season, with temperatures quickly dropping and the days growing shorter, I observed an incredible diversity of flora and fauna. By combining my in-person experiences with educational materials provided by park staff, I created a series of ten drawings that explore the life supported by Zion canyon.

Species Featured in ‘Snakes of Zion National Park:’ Desert Striped Whipsnake, Ring-necked Snake, Wandering Gartersnake, Gopher Snake, Great Basin Rattlesnake, California Kingsnake, Groundsnake, Nightsnake, Western Lyresnake, Sonoran Mountain Kingsnake, Smith’s Black-heaeded Snake, Mohave Patch-nosed Snake, Red Racer

Species Featured in ‘Common Small Mammals and Wildflowers of Zion National Park:’ Black Tailed Jackrabbit, Canyon Mouse, Cliff Chipmunk, Desert Cottontail, Golden-mantled Ground Squirrel, Rock Squirrel, White-tailed Antelope Squirrel and twenty-three plant species.

Artist Zoe Keller uses graphite and digital media to create large-scale, meticulously rendered visual narratives. Placing a special focus on at-risk species and wildlands, Keller weaves drawings that explore the interconnectedness of fragile, vanishing ecosystems. By highlighting the biodiversity at risk in an era of human-driven mass extinction their work aims to inspire reverence for the natural world and action to defend what we have left. Keller's studio work draws upon months of research, collaborations with the scientific community, and on-the-ground experiences in wild places through artist residencies and self-directed expeditions. A Woodstock, New York native, Keller has made homes and studios in Minneapolis, Philadelphia,West Michigan's farm country, Eastern Oregon's Wallowa Mountains and Portland, before finally returning to the North East. Keller currently resides in South Portland, Maine.